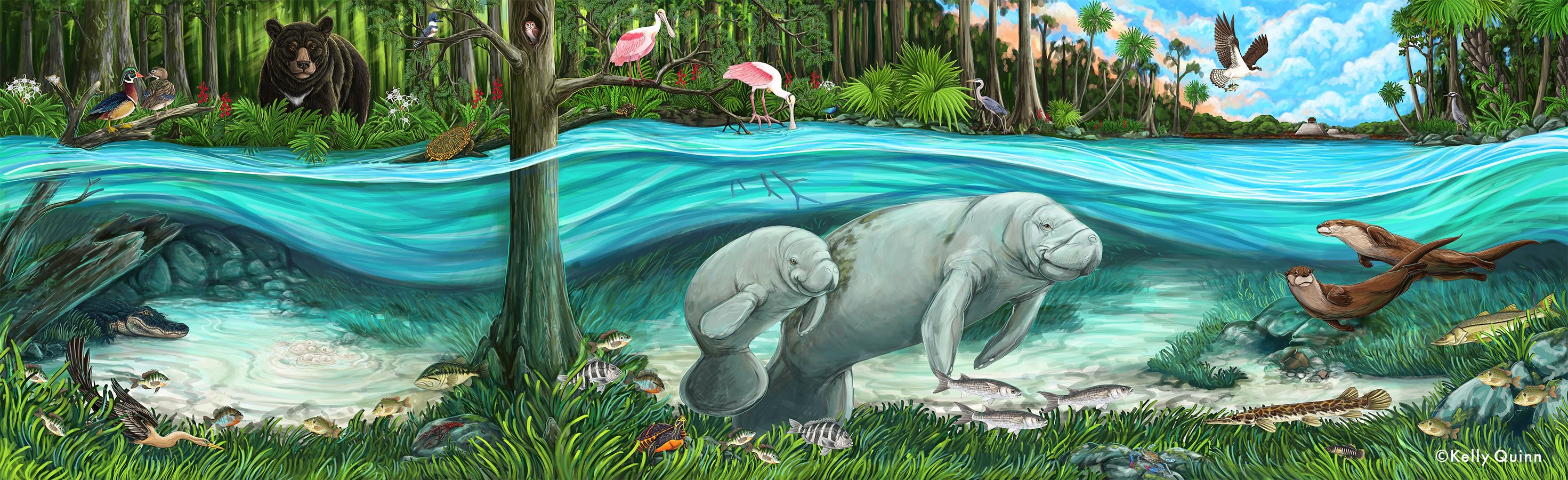

Crystal River Mural

Muralist Kelly Quinn of Canvas of the Wild

The Florida Wildlife Corridor is an 18-million-acre statewide network of connected lands and waters that supports wildlife and people.

Seen in dark green, 10 million acres are protected as Federal lands, state parks and forests, or private lands under conservation easements.

The remaining 8 million unprotected acres in light green are opportunity areas for conservation and are mostly comprised of agricultural working lands, such as cattle ranches and timber land. Not only do these valuable spaces provide food and fiber for Florida and our nation, but they also provide interconnected landscapes that keep Florida’s wild spaces connected.

Our Mural Campaign is aimed at raising awareness of the importance of the Florida Wildlife Corridor in areas with the greatest ecological significance that have the greatest risk of development by 2030.

Crystal River is a critical link of the Florida Wildlife Corridor, which supports a unique ecosystem, that plays a significant ecological role within the Corridor. How the county grows will determine the fate of wildlife, clean waters, and the natural beauty locals take pride in.

The Crystal River Mural brings awareness to greater connectedness of what locals already treasure and empowers visitors and community members alike to expand their Corridor Pride.

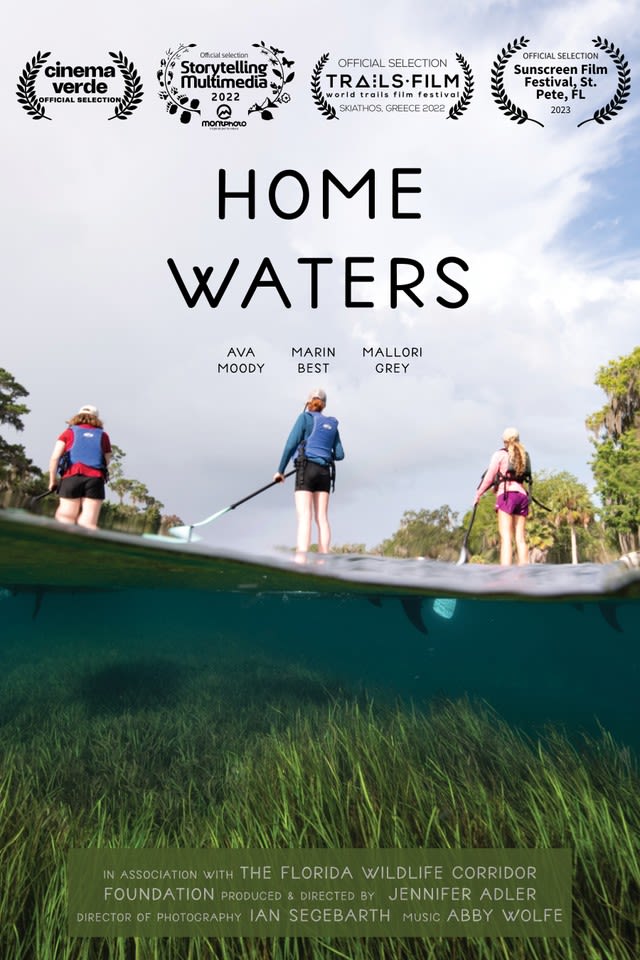

The mural builds upon the 2021 teen expedition from Rainbow Springs to Homosassa Bay, where three local High School students experienced wild Florida in their backyard. The subsequent film, Home Waters, by Jennifer Adler and Ian Segebarth, documents how their perspectives shift to understanding the importance of keeping each piece of the Corridor connected and protected. The mural is designed to inform viewers about the Corridor and inspire the continued protection of some of the most at-risk land in Florida.

Canvas of the Wild

Co-founded in 2018 by Kelly Quinn and Blake Wheeler, Canvas of the Wild is a creative design, development, and publishing studio focused on supporting STEAM education.

Canvas of the Wild engages individuals with environmental science through the creative process. Its mission is to help individuals see their relationship with a subject differently and inspire them to explore new perspectives through infographics, books, workshops, and interactive environments.

Kelly Quinn is a Florida-based artist and the Art Director for Canvas of the Wild. Born and raised in the sunshine state on the headwaters of the Everglades, Kelly’s passion for nature was sparked in childhood and has inspired her career as a professional artist dedicated to communicating science through the power of art.

“ I was born and raised on the headwaters of the Everglades, where I learned the land and water were a part of my identity, and the charismatic animals I shared my home with were my fellow neighbors, all of which had a story worthy of being shared. Today, I use art to communicate these wild stories and highlight the underlying science behind each inspiration to help form deeper connections between people and nature.”

The Crystal River Mural was made possible by the support of the following. Thank you.

Sponsors

Burt Eno, local wild Florida advocate

Citrus County Chamber of Commerce

In-Kind Sponsors

Lumen

Sunbelt Rentals

Partners

Canvas of the Wild

City of Crystal River

Crystal River Main Street

Special Thanks

Citrus County Education Foundation

The Crytal River mural showcases the unique freshwater ecosystem surrounding the town of Crystal River. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission manages fish and wildlife resources for their long-term well-being and the benefit of people. Thanks to their contributions, you can learn more about the species in this mural. Scroll to learn about each of the species featured in the mural.

Photo by Frank Abbott

Photo by Frank Abbott

Wood Duck (Aix sponsa)

Wood ducks can be identified by their crested head and broad, long tail. Males are brightly colored, while females are brownish gray.

Florida is home to year-round (resident) and migratory wood ducks. They inhabit wooded, brushy, or other vegetated wetland areas. Wood ducks nest in tree cavities near lakes, rivers, ponds, and other wetland areas.

Photo by Connor Howe

Photo by Connor Howe

Florida Black Bear (Ursus americanus floridanus)

The Florida Black Bear is one of 16 subspecies of the American black bear and is the only bear species in Florida.

Black bears prefer habitats with a dense understory such as forested wetlands and uplands, natural pinelands, hammocks, scrub, and shrub lands, but will use just about every habitat type in Florida, including swamps.

Bears are generally solitary, except when in family groups (female and offspring) or pairings during the mating season.

Photo by Marc Woodford

Photo by Marc Woodford

Belted Kingfisher

(Ceryle alcyon)

As their name suggests, Belted Kingfishers feed largely on fish, but they also eat insects, crayfish, frogs, young birds, small rodents, and even berries.

Photo by Robert Krayer

Photo by Robert Krayer

Eastern Screech Owl

(Otus asio)

A common resident throughout the state, the Eastern Screech-Owl is Florida's smallest owl. This species is found in all types of wooded habitats, including suburban backyards. Eastern Screech-Owls feed on a variety of animals including insects, lizards, mice, and small birds. They commonly nest in tree cavities, like the one shown here!

Photo by Anthony Lischio

Photo by Anthony Lischio

Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans)

The red-eared slider is native to the Mississippi River drainages. A subspecies, the yellow-bellied slider (Trachemys scripta scripta), occurs naturally in north Florida.

Red-eared sliders have been sold by the hundreds of millions in dime stores and pet shops throughout the United States. As a result, this adaptable species has become established in many areas of the world, including Europe and Japan, where they compete with native turtle species and prey upon native fish.

Photo by Alex Freeze

Photo by Alex Freeze

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

The American alligator is one of two crocodilians native to Florida. They prefer freshwater lakes and slow-moving rivers and their associated wetlands, but they also can be found in brackish water habitats and rarely in salt water.

Their diets include prey species that are abundant and easily accessible. Juvenile alligators eat primarily insects, amphibians, small fish, and other invertebrates. Adult alligators eat rough fish, snakes, turtles, small mammals, and birds.

Alligators regulate their body temperature by basking in the sun or moving to areas with warmer or cooler air or water temperatures. Alligators are dormant throughout much of the winter. During this time, they can be found in burrows that they construct adjacent to an alligator hole or open water, but they occasionally emerge to bask in the sun during periods of warm weather.

The American alligator is Federally protected by the Endangered Species Act as a Threatened species, due to their similarity of appearance to the American crocodile, and as a Federally-designated Threatened species by Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species Rule.

Photo by Bonnie Masdeu

Photo by Bonnie Masdeu

Anghina (Anhinga anhinga)

Also known as the snake bird, the anhinga is a year-round resident of Florida. You can often spot them perched on a branch with wings outstretched, drying feathers.

They feed on small fish, shrimp, amphibians, crayfish and young alligators and snakes. The fact that their feathers are less water resistant than other birds helps them to swim underwater, where they often spear fish with their long neck and sharp beak. They surface in order to flip their catch into their mouth for consumption.

Photo by Matthew Sullivan

Photo by Matthew Sullivan

Largemouth Bass

(Micropterus salmoides)

The Florida largemouth bass is the state freshwater fish. Found statewide in lakes and rivers, they are commonly found along vegetation, or underwater structure, but schooling bass are also found in the middle of lakes.

Photo by Dr Mark Cook

Photo by Dr Mark Cook

Everglades Crayfish (Procambarus alleni)

These 2-inch-long crayfish are an important food source for many of the other species featured in this mural including owls, ospreys, alligators, turtles, and otters. Restoring freshwater flows in the coastal wetlands and marl prairies will go a long way to supporting Everglades Crayfish and the species the rely on them.

Spotted Sunfish

Lepomis punctatus

The spotted sunfish (“stumpknocker”) can be found throughout Florida’s lakes and rivers. Don't let this fish's small size fool you—they are very aggressive in defending their bed during the spawning season.

Bluegill

(Lepomis macrochirus)

Bluegill are common throughout Florida but are best known in lakes and ponds. Bluegill eat mostly insects and their larvae. Bluegill spawn throughout summer, congregating in large "beds".

Redbreast Sunfish

(Lepomis auritus)

Also known as river bream and redbellies, these are the flowing water cousins of bluegill. Redbellies often can be found in backwater areas with less flow, especially where there are sandy bottoms. Common in rivers of north Florida but absent from south Florida.

Principal food organisms are bottom-dwelling insect larvae, snails, clams, shrimp, crayfish, and small fish. Compared to some sunfish, redbreasts grow slowly.

Photo by Nate Arnold

Photo by Nate Arnold

Roseate Spoonbill

(Platalea ajaja)

The roseate spoonbill is the only spoonbill endemic (native) to the Western Hemisphere. While the species looks almost entirely pink in flight, they actually have no feathers at all on their heads. The pink coloration comes from the organisms on which they feed, which are full of caroteniods (organic pigment).

As the name implies, the roseate spoonbill also has a large, spoon-shaped bill, which it sweeps back and forth in shallow water to capture prey. The specialized bill has sensitive nerve endings which help the birds search for food in shallow water. The diet of the roseate spoonbill primarily consists of crayfish, shrimp, crabs, and small fish.

The roseate spoonbill is protected by the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act and as a State-designated Threatened species by Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species Rule.

Photo by Alex Roukis

Photo by Alex Roukis

Eastern Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum)

The elusive Tiger salamander spend the majority of the year burrowed underground to escape high temperatures. Unlike most other salamanders they dig their own burrows, some even reaching 2 feet deep.

You are most likely to catch a glimpse of these salamanders at the surface after heavy rains. Worms, snails, slugs, and insects make up most of the adult tiger salamander’s diet.

Photo by Joseph Ricketts

Photo by Joseph Ricketts

Manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris)

Manatees are aquatic herbivores (plant-eaters). Also known as "sea cows," these herbivores usually spend up to eight hours a day grazing on seagrasses and other marine or freshwater vegetation, eating up to ten percent of their body weight in aquatic vegetation each day.

Like other mammals, manatees breathe air. When active, manatees must surface every three to five minutes to breathe but can hold their breath for as long as 20 minutes when resting.

Females have a 13-month gestation time, and have a low reproductive rate, giving birth to an average of one calf every three to five years. At birth, a manatee calf weighs around 60 - 70 pounds. The calf will stay with the mother for up to two years.

Prior to winter’s coldest months, manatees migrate to Florida’s warm water habitats, which include artesian springs and power plant discharge canals.

The main threats to manatees are collisions with boats and the loss of warm water habitat. Due to the inability to regulate their body temperature (thermoregulate) in cold water, cold stress is a serious threat to the manatee. Habitat loss is also an issue as coastal development and pollution can destroy seagrass beds and freshwater aquatic vegetation, which is the main food source of manatees.

The West Indian manatee is protected as a threatened species by the Federal Endangered Species Act, by the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Florida Administrative Code - Florida Manatee Sanctuary Act (FMSA) (FAC 68C-22).

Photo by Joseph Ricketts

Photo by Joseph Ricketts

Stripped Mullet

(Mugil cephalus)

Adult striped mullet migrate offshore in large schools to spawn. Juveniles migrate inshore at about 1 inch in size, moving far up tidal creeks. Frequent leapers and feed on algae, decaying matter and other tiny marine life.

Photo by Justin Grubb | Running Wild Media

Photo by Justin Grubb | Running Wild Media

Atlantic Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus)

Atlantic Blue Crabs feed on a variety of plant and animal material but prefer live or fresh prey. They habitat seagrass beds and other submerged aquatic vegetation areas are important nursery habitats for juvenile blue crabs, while adults use grassy and shallow sandy areas.

Photo by Thomas Waltzek

Photo by Thomas Waltzek

Florida Gar

(Lepisosteus platyrhincus)

Florida Gar are found in the Ochlockonee River and waters east and south in peninsular Florida where they inhabit streams, canals and lakes with mud or sand bottoms near underwater vegetation. These prehistoric fish have ganoid (bony) scales that have peg-and-socket joints forming a hard armor.

Photo by Stephanie Smith

Photo by Stephanie Smith

Great Blue Heron

(Ardea herodias)

Keep your eyes peeled for Great Blue Herons poised at river bends or cruising the coastline with slow, deep wingbeats. Great Blue Herons eat mainly fish, but have also been known to consume frogs, salamanders, turtles, snakes, insects, rodents, birds.

Muralist Kelly Quinn outlining her otter design on the Crysal River mural wall.

Muralist Kelly Quinn outlining her otter design on the Crysal River mural wall.

River Otter (Lontra canadensis)

The river otter is adapted for both land and water with short legs, webbed toes, and a strong, flattened tail. This water-loving animal is found throughout Florida except the Keys. River otters usually prefer fresh water and can be found in rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, and swamps. Otters live in burrows on the bank of the water body, often under tree roots. They may dig their own burrow or remodel a beaver’s burrow.

They are social animals, and groups usually consist of a female and her juvenile offspring.

Photo by Anthony Meugenio

Photo by Anthony Meugenio

Photo by Montgomery Avidon

Photo by Montgomery Avidon

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus)

Several features distinguish the osprey from other birds of prey, including a reversible fourth toe and spines located on their feet that are used to help grasp their prey as they fly over the water. The undersides of the toes on each foot are covered with short spines, which help them grasp slippery fish.

The osprey is found year-round in Florida both as a nesting species and as a spring and fall migrant passing between more northern areas and Central and South America. Pesticides, shoreline development and declining water quality continue to threaten the abundance and availability of food and nest sites for ospreys.

In Florida, ospreys commonly capture saltwater catfish, mullet, spotted trout, shad, crappie, and sunfish from coastal habitats and freshwater lakes and rivers for their diet.

Ospreys build large stick nests located in the tops of large living or dead trees and on manmade structures such as utility poles, channel markers, and nest platforms.

The osprey is protected by the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Although it is no longer listed as a Species of Special Concern, it is still included in the Imperiled Species Management Plan. Inactive nests (i.e., nests without eggs or flightless young) can be removed without a permit.

Photo by Mac Aldrich

Photo by Mac Aldrich

Yellow-crowned Night Heron (Nyctanassa violacea)

Yellow-crowned Night-Herons forage at all hours of the day and night. Their diet consists mainly of crabs and crayfish. They’re most common in coastal marshes, barrier islands, and mangroves.

Photo by Senza Nome

Photo by Senza Nome

Purple Gallinule

(Porphyrio martinica)

You can find these colorful birds in the extreme southeastern U.S. These long-legged, long-toed birds step gingerly across water lilies and other floating vegetation to hunt frogs and invertebrates or pick at plant tubers.